Group Theory 0 - Dihedral Group of Order 2n

Do you like group theory?

I’d like to start a series of expository blog posts that “climb up the chain” of the dihedral groups of order \(2n\) (as in, what do these groups visually look like as we vary \(n\) from \(1\) to \(n\)) in way more detail than what I’ve found in textbooks and other online resources.

A danger to this is some readers will find this exercise uninteresting since the dihedral group (in particular \(D_8\), the group of symmetries of the square under reflection \(s\) and rotation \(r\)) is one of the first examples of groups in a ton of textbooks, but I have yet to find a comprehensive walkthrough of the first few \(n\) for \(D_{2n}\) (this is because in almost all references, \(D_{2n}\) is defined for \(n\geq 3\), but the presentation still holds for lower group orders).

First, let’s name names: When I say \(D_{2n}\) I mean the group of symmetries of the \(n\)-gon in Euclidian space under the operations of translation and reflection, for \(n \geq 3\). For \(n=1,2\), I will call them \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), respectively (in the geometric convention). For \(n \geq 3\), I will call the dihedral groups \(D_{2n}\).

I’m sure we’ve all been presented with pictures of polygons as children and been asked to count its symmetries. Well, the formal exploration of these groups is just like that, except we’re going to find additional sub-structure on these symmetries in the form of subgroups.

That’s what the interesting question here is: Given a dihedral group, what are its subgroups?

I hope to build up to this fairly quickly, at least as fast as I’m presenting them.

Let’s start.

\(D_1\) - Dihedral Group of Order 2

Here we start with the case that \(n=1\), the \(1\)-sided polygon. This group is called \(D_1\).

This the group of the symmetries of the \(1\)-sided polygon in Euclidian Space, under the operations of reflection \(s\) or rotation \(r\).

The only possible move here is to “switch the vertices”, or reflect across the midpoint of the polygon. Equivalently, you can rotate the line \(180\) degrees about the midpoint and get the same symmetry. In either case, let’s call the operation “switching the vertices”.

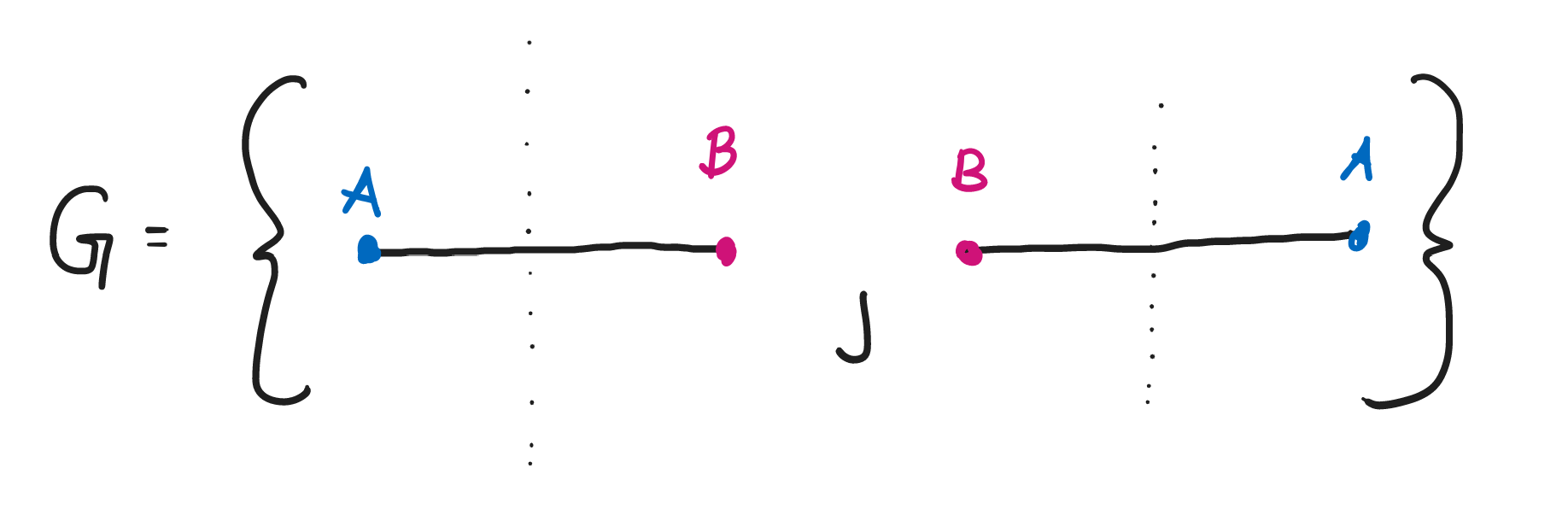

So, \(D_1\) looks like the set of these two symmetries:

We have identity \(e\) (leaving the \(1\)-sided polygon as is), and the image of \(s\) about the midpoint or \(r\) by \(180\) degrees.

Intuitively, \(D_{1}\) is also called the symmetry group of the line segment.

Presentation of \(D_1\)

In general, the presentation of \(D_{2n}\) for \(n \geq 3\) is:

\[D_{2n} = <r,s | r^n = s^2 = 1, rs = sr^{-1}>\]so that rotation \(r\) and reflection \(s\) are the two generators, and we have the relations listed on the right side of the pipe.

But as we will see, this presentation also holds for \(n=1,2\).

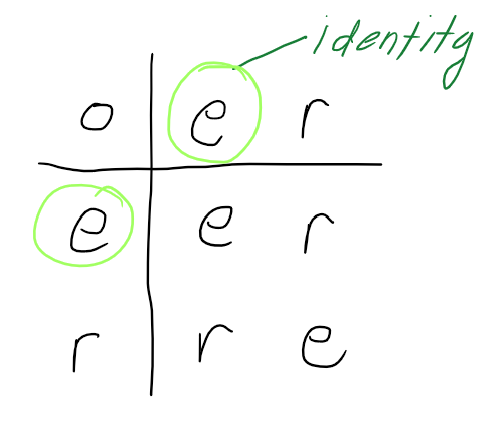

The Cayley Table of \(D_1\) is:

where \(r\) is rotation by \(108\) degrees.

The the group is Abelian and isomorphic to all groups of order \(2\).

What About Subgroups?

By Langrage’s Theorem, we have that the order of any possible subgroups must divide the order of the group. So the only possible subgroups have orders \(1,2\).

Then we have the trivial subgroup \(G = {e}\) and the group itself.

A Note on the \(1\) sided polygon

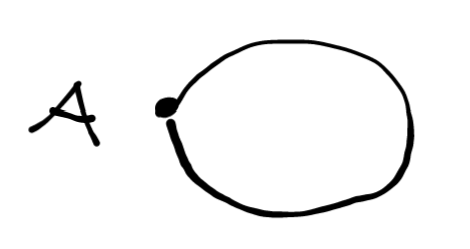

In Artin’s Algebra, he describes the 1-gon as a single node with a loop. Like so,

I found it difficult to represent the symmetries with this visualization of the polygon, so I went with the two vertex drawing. They both represent \(D_1\).